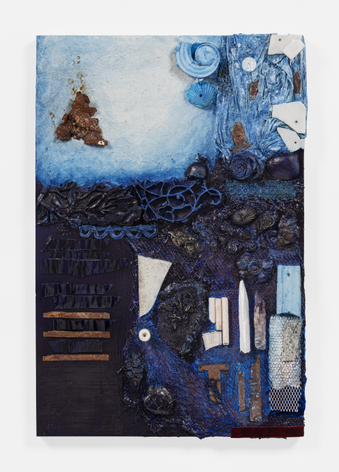

Asya Geisberg Gallery is proud to present “Looking Glass,” an exhibition of sculpture and installation by Julie Schenkelberg. Born and based in Cleveland, the artist has long made the industrial Midwest a rich vein for her sculpture, recently adding the shore of Lake Erie to point towards the pastoral. She cuts invasively into buildings and furniture, plunges into hazardous places by sourcing discarded materials from scrap yards, construction sites, abandoned factories, or finding once revered domestic objects from estate sales. Such heterogeneity of scale, texture, and origin is transformed in unexpected combinations as the work mixes high value materials like marble and gold leaf with inauspicious rusted metal or wire mesh. Schenkelberg’s juxtapositions seem hauntingly familiar, regenerating the lost beauty of decaying or forgotten narratives.

The show’s title could mean a mirror from the 19th century with sufficient reflection but not fully clear, a portal into an alternate reality, à la Alice, or a dulled memory of the past. Schenkelberg is an an archaeologist, an archivist of the crumbled and broken, and a historian of former industries and economic heydays, both individual and regional. Yet her sculptures become so thrillingly alive that we see obsolete electrical porcelain tubes rendered as bones, springs glowing with autumnal rust coiled into a tiny helix, clocks, dishes, or bottles as memento mori of the domestic. More figurative elements have been cropping up in Schenkelberg’s work in plaster cast from cemeteries or palatial homes, imbued with rich marine blues or shipwreck greens. To Schenkelberg, the blue is otherworldly, ghostly, royal, and luminous like medieval stained glass. Much like the obscured reflection of the looking glass, the liquid imagery is an unsettling holder of deep secrets or hidden truths, unifying the disparate elements in a portal to the unknown. Similarly, through symbols such as a rose wreath, daisies, and a reliquary pointing hand, the artist charts a coded language of the unseen world.

At times, the broken chiselled fragments clump together, accreting in an archaeological sedimentation. In larger works the accumulations take over most of the surface, with round clocks or trays resembling a sun or moon within. The search for her materials is a reverent excavation, while the resulting work skims the line between order and disorder, excess and poverty, utility and disuse, or vitality and decrepitude. As her laundry list of media makes clear, a poetry emerges: rebar, velvet, burlap, buttons, shells, tiles, factory glass, iron, and even a draping sail cloth frozen in its undulation in the site-specific installation “Wreckage.” Schenkelberg’s reconfigurations and aggregations unearth the buried histories around her, while revelling in the murk.